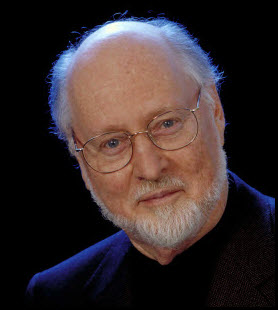

The recent release of John Williams seventh Star Wars score for Star Wars: The Force Awakens (2015) coincided with me having some extra free time and the desire to write more here on my strange WordPress. That convergence of planets resulted in me reflecting on both my early memories of music and the subsequent formation of my musical tastes which largely involve a penchant for instrumental music. John Williams’ music in general, and in particular his score for the first Star Wars film (1977), played an important role in the formation of those musical tastes, and his music continues to this day to be a regular and cherished part of most days.

All of my earliest memories of music are of the music of John Williams. I recall sitting in a theater as a child but not what movie I was there to see. From the adjoining theater during the brief silence before the main feature began, the thundering but muffled sounds of Williams’ “Superman March” could be heard:

I recognized the music and longed to be in that theater to better hear those glorious sounds. Since I recognized the music, I must have already had seen Superman The Movie (1978), but I do not remember seeing it that first time. That’s my earliest memory of being captivated by the thing we call music. I was five going on six.

A few years later, I began guitar lessons with Peter Duggan, a multi-instrumentalist who is currently the Adelaide Symphony Orchestra’s principal cor anglaisist. As fate would have it, Peter was, and probably still is, a big fan of John Williams. Peter would make guitar arrangements of Williams’ most famous themes and incorporate them into our lessons. He made an arrangement of the theme from Jaws (1978) for solo guitar and an arrangement of the Star Wars theme for two guitars which we played at a school recital circa 1982, my first public performance. Master Yoda was right when he said: “Always two there are, no more, no less. A master and an apprentice.” I’m still very much the apprentice.

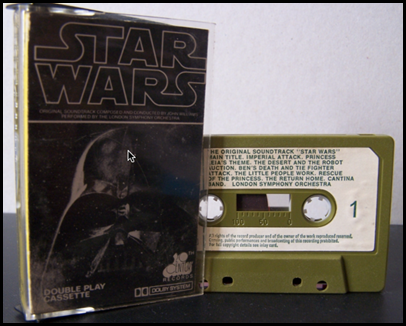

Peter lent me his double cassette of the Star Wars soundtrack probably around the time I was learning to play his arrangement. Listening to it was the first time I had listened to music at home that didn’t emanate from the radio or music collections of my elder brothers and sisters. I don’t recall my siblings listening to orchestral music or having classical music in their collections, so the first music I enjoyed privately at home was the music of John Williams performed by the London Symphony Orchestra.

What fascinated and surprised me when listening to the Star Wars soundtrack was not the iconic main theme; rather, it was the other diverse elements of the score such as the quirky music for the Jawas, the atonal music for the Sand People, the 1930s big bandish “Cantina Band”, and the lush romanticism of “Princess Leia’s Theme”. The varied music of Star Wars served as an introduction to both the vast soundscape available to an orchestra and to the diversity of Williams’ craftsmanship and mastery of music.

In the early 80s on the Mike Willesee current affairs show, I encountered John Williams again via a story about a young boy dying of cancer who loved the music of John Williams. I remember being moved by how much joy Williams’ music had given the dying boy. The music of ET, which was a fairly recent movie at the time, was played during the segment. Once again, I found myself captivated by Williams’ melodies. The ET theme soon all but disappeared from my memory. Like an almost forgotten dream, I could recall the emotions the music conveyed, but not the specific notes. Now of course, those notes are but a few key strokes away:

I gradually began noticing music more while watching movies and TV and started recognizing the names of film composers prolific during that period. I would often seeing the words “Music by Jerry Goldsmith” on movie screens and on TV screens during the 80s. It seemed like his name was attached to every second movie I saw. Rambo: First Blood Part 2 (1985) which I saw in a cinema and Capricorn One (1978) which I saw on TV are two examples that have stayed in my memory. Looking back now, I’m surprised that it never occurred to me to seek out soundtracks, but I was quite young at the time, and the idea of buying anything, let alone music, hadn’t yet arisen.

I bought my first CD player in 1988 and along with it my very first CD – a CD player isn’t much use without one. My first CD was Bruce Springsteen’s Tunnel of Love (1987). Bruce’s classic Born in the USA (1984) album was the very first record I listened to and enjoyed from start to finish. I found it while rummaging through my sister’s LP collection. I was fascinated by the combination of the stories the lyrics told and the polished craftsmanship of Springsteen’s compositions and arrangements. I was initially drawn to the album because of the megahit “Dancing In The Dark” with its memorable video featuring a young Courtney Cox 12 years before Friends:

I still enjoy Springsteen and the music of many other artists of the 70s and 80s, the decades of my childhood, so it’s not like I dislike songs, I am just more attracted to melodies and harmonies. Songs that I do like, I like largely for those aspects. In fact, I recall playing for a friend a song I quite liked and being surprised when he responded he didn’t like it because the lyrics were “corny”. That took me by complete surprise because, in all honesty, I hadn’t really paid attention to the lyrics; the elements of the song that had appealed me were its melodies, rhythms, instrumentation, and harmonies. I found it both interesting and baffling that I had hardly thought about the lyrics at all while they were essentially the only element my friend noticed and based his opinion of the song on.

In his book The World in Six Songs, musicologist Daniel J. Levitan touches upon that very subject – the differing preference levels people have for the musical and lyrical aspects of songs (I like reading books about music almost as much as I like listening to music):

Still, it is important to note that some people ignore the lyrics more or less, and are drawn primarily to rhythm and melody.

Guilty.

Even in pop, jazz, hip-hop, and rock, legions of people believe that the lyrics function primarily as an afterthought, something to hand the melody on. “They’re just there so that the singer doesn’t have to go ‘la-la’ with the melody all the time.”

Well, I wouldn’t go that far, but it’s safe to say that if tested, I would score quite high on the musical preference axis and closer to zero on the lyrical.

Soon after I began buying CDs, an instrumental artist whose music I would also go on to admire and to enjoy to this day was just starting to make a name for himself. Joe Satriani’s Surfing With The Alien (1987) was introduced to me by my second guitar teacher, jazz musician Cole Bernau. It was my first all-instrumental CD. Looking back, it most definitely helped awaken my preference for instrumental music. On a side note, Steve Vai, Satriani’s star pupil, would soon join my list of favourite musicians.

Like John Williams, Joe Satriani (and Steve) is still producing great music to this day, and my enjoyment and appreciation of his music has likewise only grown over the decades. Here are two tracks separated by 28 years: “Always With Me, Always With You” from Surfing With The Alien and the title track from Shockwave Supernova (2015) an appropriate piece to mention as the detection of gravity waves was announced the day I wrote this sentence.

Looking back with hindsight’s , some of the rock music I enjoyed in my teenage years suggested a nascent taste for instrumentals. Brain May’s guitar solos and overall playing appealed to me as did the sophisticated song writing skills of Freddie Mercury and his other Queen colleagues. Dire Straits‘ live double CD Alchemy was another album that I loved early in my musical explorations for its instrumental passages. Alchemy features several extended instrumental sections that showcase the melodic and rather unique guitar of Mark Knopfler, himself a composer of soundtracks including Local Hero (1983), Cal (1984), and The Princess Bride (1987). One of the instrumental sections which captivated me the most starts at 6:40 “Tunnel of Love”:

It took a music book of solo arrangements of film themes for guitar to rekindle my interest in the symphonic sounds of John Williams and to begin buying soundtracks. I had long admired “Cavatina” from The Deer Hunter soundtrack by Stanley Myers ever since hearing it perform it at a school assembly when I was 11 or 12. It’s a piece that never fails to relax me when I play it; it’s a meditation. Here is guitarist John Williams (no relation) performing it, and below that, one of my own attempts from 5 years ago in a candlelit room with a very special friend accompanying me on piano:

In 1989, I came across a book called Cavatina & 20 Movie Themes for Solo Guitar that not only contained “Cavatina” but also an arrangement of “Can You Read My Mind?”, the love theme from Superman The Movie. I still have it with me in fact:

I could hum Superman’s main theme but not the love theme. I was very curious to hear it, so I immediately bought the book and rushed home to play it. When I played it for the first time, the melody was both instantly recognizable and instantly captivating; love at first listen.

I could hum Superman’s main theme but not the love theme. I was very curious to hear it, so I immediately bought the book and rushed home to play it. When I played it for the first time, the melody was both instantly recognizable and instantly captivating; love at first listen.

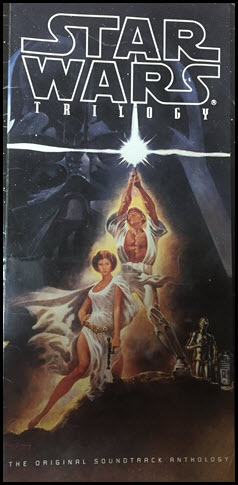

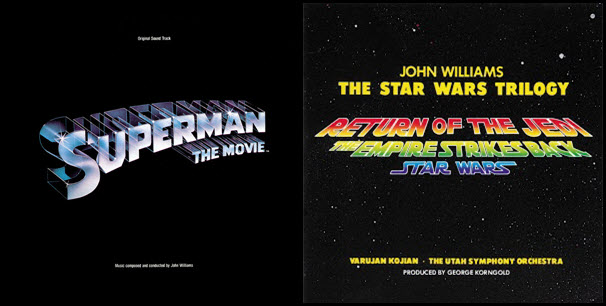

Playing “Can You Read My Mind” on guitar inevitably led me to seek out the soundtrack as I was eager to hear the original orchestral performance. I ventured to Impact Records, Canberra’s largest record store at the time, and went straight to the soundtrack section. I wasn’t entirely sure it would be there, but the Soundtrack God’s were smiling on me that day. There it was in the “S” section. I picked it up and immediately noticed that the CD behind it was “The Star Wars Trilogy”. Like my first look at the the guitar arrangement of “Can You Read My Mind?”, I was intrigued by track titles such as “Luke and Leia”, “Yoda’s Theme”, and “The Forest Battle”. I knew and loved the famous “The Imperial March (Darth Vader’s Theme)”, but the majority of the other tracks, apart from the main theme of course, were beyond recall.

I hadn’t gone to the store expecting to buy two CDs, and I was a little short of cash at the time. The dilemma I was unexpectedly faced with was a huge one; the result was several stressful and indecisive minutes trying to decide which one to buy before inevitably succumbing to music’s irresistible temptation. Yoda said that there are always two.

I hadn’t gone to the store expecting to buy two CDs, and I was a little short of cash at the time. The dilemma I was unexpectedly faced with was a huge one; the result was several stressful and indecisive minutes trying to decide which one to buy before inevitably succumbing to music’s irresistible temptation. Yoda said that there are always two.

Those purchases represented both a mile stone and a turning point in my musical journey: 26 years later, I’m still buying and loving the music of John Williams; 26 years later, the gentle openings of the “Love Theme from Superman” and “Yoda’s Theme” still give me goosebumps:

Not long after, I saw JFK (1991) with my sister at a cinema in Sydney. Seeing “Music by John Williams” in the opening credits came as a complete and very welcome surprise. Consequently, I paid extra attention to the score; I especially remember noticing the lovely and gentle family theme Williams wrote to represent the love the main character and his young family share. I wasn’t yet at the stage where every Williams soundtrack was an automatic purchase, but I recall hearing that piece and immediately deciding I needed the soundtrack.

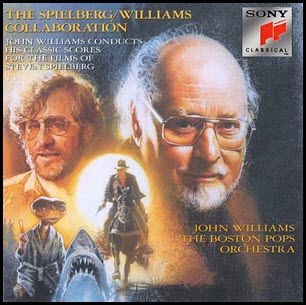

Another important CD in that early period of discovery was The Spielberg/Williams Collaboration (1991) which contained re-imagined arrangements for concert performance of both his famous and less famous pieces from his scores for Steven Spielberg.

That CD introduced me to more musical gems such as his suite from Always (1989) and “Cadillac of the Skies” from Empire Of The Sun (1987). They offered proof that John Williams had written amazing music for films I had either never heard of or had barely noticed. What other musical gems existed amongst Williams’ already vast body of work? That was a question I was eager to answer, and it turned out, not surprisingly, that there were more than a few musical gems waiting for my ears to discover, hear, and enjoy. Williams has, after all, been composing music since the 1950s.

That CD introduced me to more musical gems such as his suite from Always (1989) and “Cadillac of the Skies” from Empire Of The Sun (1987). They offered proof that John Williams had written amazing music for films I had either never heard of or had barely noticed. What other musical gems existed amongst Williams’ already vast body of work? That was a question I was eager to answer, and it turned out, not surprisingly, that there were more than a few musical gems waiting for my ears to discover, hear, and enjoy. Williams has, after all, been composing music since the 1950s.

Those first soundtracks awoke in me a hunger for all things Williams. I began scouring soundtrack sections of music stores in Canberra and Sydney and on my later travels in London, New York, Kyoto, and Bangkok. The Internet had yet to exist, so my initial sources for information on what scores John Williams had written were music stores and cinema movie posters. I couldn’t pass a new movie poster without squinting to read the fine print following the words “Music by”. It was nice when that squinting was rewarded with Williams’ name or the names of other film composers I was beginning to notice, namely Jerry Goldsmith and James Horner.

In those pre-Internet days, my enjoyment of soundtracks was a solitary pursuit. For a while there early on, it felt like I was the only John Williams’s fan in the world. Of course I wasn’t, but I certainly was in my circle of friends. It was quite a surprise then when I heard John Williams music on the radio for the first time. It was a Sunday night back in the early 1990s. I was driving my uncle’s taxi and scrolling through FM radio stations when I happened upon some familiar music on a classical music station that I couldn’t for the life of me identify. I knew I knew it, but trying to identify it left me totally stumped. The name of the piece was on the tip of my tongue and on the end of my ear.

When the piece ended, the announcer saved me from insanity by providing the answer: John Williams’ score for Dracula (1979). I tuned in the next week at the same time and the next and the next. My listening loyalty was rewarded with introductions to composers new to me, in particular Elmer Bernstein via his rousing theme for The Magnificent Seven (1960) which I only knew from its famous use in Marlboro Cigarette ads.

Not surprisingly, I started noticing music in movies more. I always had to some extent, but now I was listening with a view to buying more soundtracks and discovering the music of other composers. James Horner’s Star Trek 2: The Wrath of Khan (1982) and Star Trek 3: The Search for Spock (1984) were early non-Williams purchases as was Michael Kamen’s Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves (1991). Bill Conti’s iconic scores for Rocky (1976) and Rocky 2 (1979) quickly came to mind when I thought of other film themes I knew and wanted to hear. Medicine Man (1991) was my first Jerry Goldsmith soundtrack following a viewing of the film with my mother. We would later both have the pleasure of hearing him give a talk in London in 1997. Medicine Man, which remains a favourite to this day, was quickly followed by Rudy (1993), which also remains a favourite to this day, and Star Trek: The Motion Picture (1979), ditto.

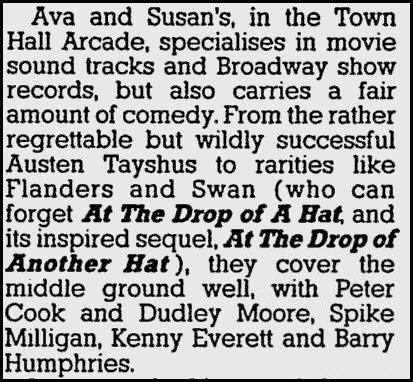

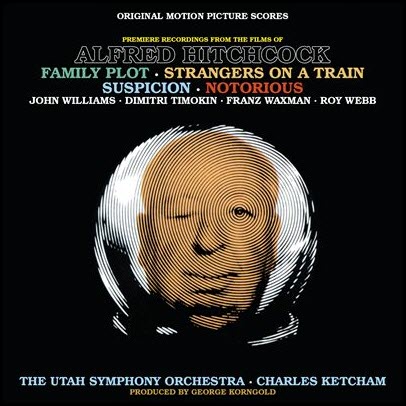

Another boost to my soundtrack interest came via a segment on TV that I caught by chance or destiny. The hosts of SBS TV’s The Movie Show were talking about Alfred Hitchcock when I happened to tune in. I stayed on channel and was soon rewarded with mention of a soundtrack specialist store in Sydney called Ava and Susan’s that stocked a compilation CD of music from the films of Hitchcock. What sparked my interest was the fact that the CD included a piece from the score to Hitchcock’s last film, A Family Plot (1975). I think it rather fitting that Hitchcock’s last picture was scored by John Williams. It was as though Hitchcock, in choosing Williams, was announcing a changing of the Hollywood guard and the ushering in of a new era.

I called Ava and Susan’s and soon became acquainted with Barry, one of its owners. Over the next few years, I bugged Barry repeatedly to enquire about scores old and new I had ordered from him. “Has it arrived yet? Has it arrived yet? Has it arrived yet?” During those years, every trip to Sydney just had to include a visit to his store to pick up scores and to browse the racks. A whole store dedicated to soundtracks was then and still is my idea of heaven. I’m grateful I got to experience heaven because it wasn’t to last. Ava and Susan’s is unfortunately long gone; references to its existence are surprisingly rare. Here’s a brief blurb from an archived 1986 newspaper article about notable Sydney music stores:

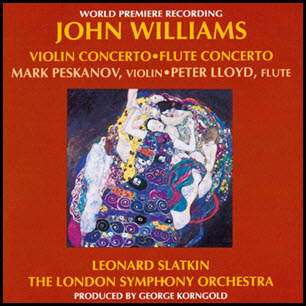

My Williams collection slowly – and sometimes not-so slowly thanks to the above – grew over the years as did my awareness of Williams distinguished, varied, and rather long career. Of particular interest to me was music Williams had written away from Hollywood. To date (early 2016), he has written twelve concerti for flute, cello, harp, bassoon, oboe, clarinet, trumpet, horn, tuba, viola, and two for violin as well as numerous pieces for soloists, chamber ensembles, and orchestras.

Williams’ flute concerto and violin concerto were my first introductions to his non-film work outside such celebratory pieces like his “Olympic Fanfare and Theme”, composed for the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics, and “Liberty Fanfare”, composed for the Statue of Liberty’s 100th birthday two years later. In terms of melodic accessibility, those two pieces are very much in the same vein as his most famous and rousing film themes, so it’s not all that surprising that I expected the same from his flute and violin concerti.

When I first heard he had written a flute concerto, I immediately recalled the romantic and lush “Princess Leia’s Theme” with its beautiful lines for solo flute. I also had a Mozart flute concerto in my collection and imagined Williams’ flute concerto somehow combining the two into a stunning and beautiful melodic feast. When his Concerto for Flute (1968), combined with his Concerto for Violin (1974), finally found its way into my CD collection courtesy of soundtrack specialists Varese Sarabande, I listened to them for the first time with an extra sense of anticipation and excitement. It was my first time listening to John Williams the composer as opposed to his alter ego, John Williams the film composer.

My first listen of the flute concerto can only be described as jarring. It did, however, reinforce and deepen my understanding of the range of Williams’ musical sensibilities, which is a polite way of saying I hated it. Safe to say it sounded about as far from my naive expectations as possible; in fact, parts of it sounded random. If John Williams “sound” is encapsulated by his Star Wars scores (and it isn’t), then his flute concerto is from a galaxy far, far away. It has, however, since grown on me somewhat over repeated listens.

My first listen of the flute concerto can only be described as jarring. It did, however, reinforce and deepen my understanding of the range of Williams’ musical sensibilities, which is a polite way of saying I hated it. Safe to say it sounded about as far from my naive expectations as possible; in fact, parts of it sounded random. If John Williams “sound” is encapsulated by his Star Wars scores (and it isn’t), then his flute concerto is from a galaxy far, far away. It has, however, since grown on me somewhat over repeated listens.

In its defence, it was inspired by the sounds of traditional Japanese flutes, so it should have come as no surprise that it sounded non-Western and strange to my entirely Western ears that were, despite the clear CD liner notes, quite ignorant of the concerto’s inspirations. In those notes, Williams’s revealed that he wanted the solo flute to sound improvised; it is no wonder I thought it sounded random – not that “improvised” equals “random” of course, but in striving for an improvised sound, Williams employed different writing techniques than the ones he would normally employ when creating a theme intended to be remembered over the course of a film. And regarding the accompaniment, Williams described it as “mysterious sounds like the snapping of branches while we explore some imaginary mythical forest.” Again, my expectations were far removed from reality.

I listened to the flute concerto recently for the first time in well over five years and was surprised how my reactions to the music have changed now that I am more accustomed to Williams broader oeuvre beyond Hollywood. I heard in it more music than the random notes and noises of my first listen, and a lot of it was now quite familiar despite it being a piece I rarely listen to.

Still on the topic of Williams’ flute concerto, pianist Daniel Wachs recently visited Williams’ home to help flutist David Buck prepare for a recent recording of it with the Detroit Symphony Orchestra under conductor Leonard Slatkin who originally recorded the piece and is now part-way through the long process of recording every Williams concerto. Mr. Wachs offers this fascinating reflection of the experience of discussing and practicing the piece with Williams in his own living room, which he rightly titled “We’re Off to See the Wizard”.

The violin concerto was more to my tastes and expectations, but it still sounded quite different from his film work. That also shouldn’t have come as a surprise as, after all, a film score and a concerto are entirely different beasts. Of the concerto’s three movements, the second movement is closer to Williams’ film work perhaps because the emotions it conveys – a sense of loss and longing – are emotions that are often called for in cinema. The second movement sounds to me like a love theme from a tragic love story. Perhaps that’s what it is as Williams dedicated the concerto to the memory of his first wife, actress, Barbara Ruick, who died in 1974, the year the concerto was composed. In fact, it was at her urging that he began work on the concerto. Williams recent trip to Boston from his home in L.A. to attend a performance of the concerto suggests it is still very much a piece close to his heart.

Not all of Williams’ concerti are so far from his more widely recognised styles. “The Five Sacred Trees”, Williams’ bassoon concerto, is my favorite Williams concerto because it is more melodic and hence closer to the John Williams I first became a fan of.

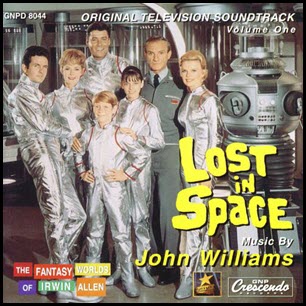

Another surprising window into Williams’ vast musical world came via the themes and early scores he wrote for the classic sci-fi TV show Lost in Space (1965).

I watched the show as a child and remember loving its main theme. I would learn later that there were actually two main themes, both written by John Williams: the first for seasons one and two and a second, and very different theme, for the final third season. It was the season three theme that I remembered most fondly, but the first theme sounded familiar when I heard it. Here’s the third season theme and below it the less serious and kind of goofy earlier theme:

Apart from those themes, I really didn’t expect the music to be familiar at all as it had been so long since I had seen an episode and I was quite young at the time. While the above themes are forever linked to the show, they did not appear in Williams’ episode scores; he avoided the first theme and had yet to write the second. Furthermore, while his music was tracked into later episodes, Williams only scored four early season episodes – that’s four episodes out of a total of 73.

Despite only writing music for a fraction of the show’s episodes, the music he did write was instantly familiar, and I found myself recalling melodies and motives I had no recollection of ever remembering in the first place. It was like I had last heard the music only a few weeks before. Williams has often said one goal is to create music that feels like it could only belong to its particular film. He certainly accomplished that with his Lost in Space music. I was also pleasantly surprised to learn that Williams also contributed themes and pilot scores for two other classic sci-fi shows from the same era: The Land of the Giants (1968) and The Time Tunnel (1966).

While John Williams, Jerry Goldsmith, and James Horner were my three favorite composers, I knew precious little about them aside from some of the movies they had scored and from what I could gleam from them from occasional liner notes which often focused more on the music and the film rather than the composer. At the Australian National Library when I should have been doing university assignments, I couldn’t help entering the names of my favored composers into the library’s database. My procrastination was rewarded with the discovery of a few books that mentioned Williams and Goldsmith. I cannot remember what they were, but I remember one contained an unflattering review of Williams’ The Empire Strikes Back score which criticised it for using the romantic symphonic idiom instead of futuristic-sounding synths and avant-garde compositional techniques. That left me totally baffled as I felt Williams’ choices were perfect, and I don’t think I’m alone in that assessment. Never mind the fact that Star Wars is set in the distant past.

Another book offered a list of Williams early scores, most of which I had never heard of before. That list was my first introduction to Williams’ early “whacky” 60s comedy period which included such non-classics like Bachelor Flat (1962), Johnny Goldfarb, Please Come Home (1965), Not With My Wife You Don’t (1966), and A Guide for the Married Man (1967). I never expected when first reading about them that I would one day own those scores, but they are all now in my collection and on my iPhone thanks to recent restoration efforts by soundtrack specialty labels like Film Score Monthly and Intrada. While those soundtracks don’t get played too often, each contains several early fun gems that are, well …. just plain fun. When I cook, which isn’t often, such pieces provide the soundtrack:

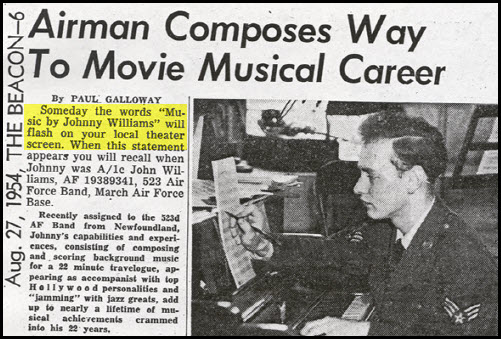

Going back in time ever further to 1955 when John was just 23 – the same age as my university students – the bright future that awaited him was prophesied:

The travelogue mentioned above was recently unearthed. Williams said of that early work: “It was not an original score. I did not have a clue or an idea on how to do that. What I did was go to the library, it must have been in St. John’s, and pick a Newfoundland folk song or two which formed the basis of what I arranged for that little film.” Here it is, and it really is a glimpse into an earlier age. I particularly love the starting cigarette:

The travelogue mentioned above was recently unearthed. Williams said of that early work: “It was not an original score. I did not have a clue or an idea on how to do that. What I did was go to the library, it must have been in St. John’s, and pick a Newfoundland folk song or two which formed the basis of what I arranged for that little film.” Here it is, and it really is a glimpse into an earlier age. I particularly love the starting cigarette:

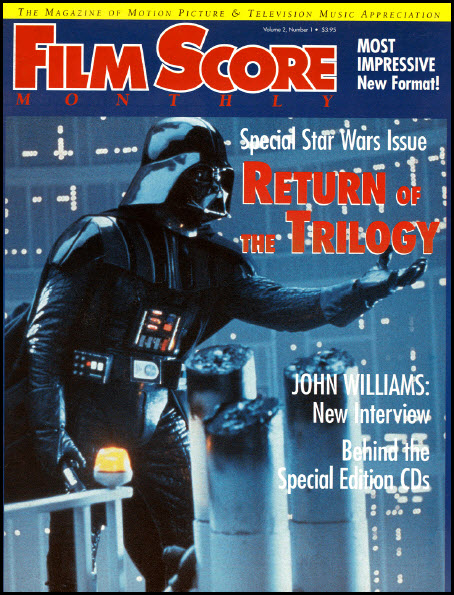

Returning to more modern and civilised times, I left Australia (and most of my music collection) in 1997 to seek fame and fortune in the UK with a two-year working holiday visa stamp in my passport. Thanks to good timing and the kindness of the Soundtrack God(s), my working holiday proved beneficial to my soundtrack collecting hobby. Recall that I had asked my local newsagent in Canberra about Film Score Monthly Magazine and that he had never heard of it. Well, a copy of the latest edition at the time (early 1997) caught my eye from the display window of a small soundtrack specialist store I just happened to walk past while exploring the area around London’s Russell Square. True story. That issue is now online here.

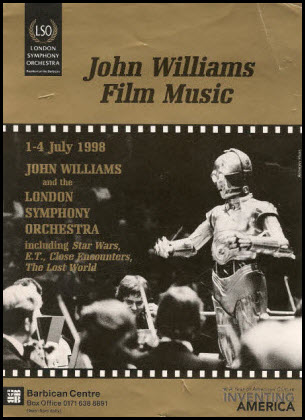

My UK stay also coincided with a rare and important soundtrack event. In 1998, John Williams travelled to London to perform four concerts with the London Symphony Orchestra at the lovely Barbican Center. I went to every single one plus the one and only open rehearsal on the Friday morning. The chance to experience John Williams in concert was simply not something I could pass up. Only death could have kept me away. It was literally a dream come true.

In the hours before that first concert, I killed some slow-moving time by walking about Kensington Gardens with Williams’ music blaring through my ears. In particular the end credits from Far and Away (1992) raised my spirits and excitement level to impossible, never-to-be-repeated levels.

The highlights of the concerts are too numerous to mention; instead, it’s easier to describe the whole experience as one mega highlight. If I had to name a few though: one was the moment Williams looked at me and smiled. Well, at the very least he looked in my general direction, and I could have sworn we made eye contact as he smiled. It felt incredible and surreal to make eye contact with the man behind the music that had so often filled my head with divine sounds and pleasure.

The highlights of the concerts are too numerous to mention; instead, it’s easier to describe the whole experience as one mega highlight. If I had to name a few though: one was the moment Williams looked at me and smiled. Well, at the very least he looked in my general direction, and I could have sworn we made eye contact as he smiled. It felt incredible and surreal to make eye contact with the man behind the music that had so often filled my head with divine sounds and pleasure.

One aspect of the concerts I was particularly excited about was hearing for the first time “Sound The Bells”, “Celebrate Discovery Fanfare” and the aptly named Tuba Concerto. If I had had an iPhone back then, I certainly would have risked a secret recording. It would be four years before those pieces were released on CD. The wait was a long one. I remember humming parts of the first two pieces at the intervals, but over time their melodies all but vanished from my memory until I could experience them on CD. Other highlights include the unexpected encore performance of “Hell’s Kitchen” from Sleepers (1996), “The Lost World” which thundered through the concert hall like a rampaging T-Rex, “The Asteroid Field” from The Empire Strikes Back (1980), and the beautiful and heartbreaking strains of “The Theme from Schindler’s List“ (1993). I was in soundtrack fandom heaven.

The open rehearsal provided the chance to actually see Williams at work. It was fascinating hearing his instructions to the orchestra as they rehearsed entire pieces certain passages. I particularly liked hearing a piece start from somewhere in the middle, at say bar 170 for example. It was just cool to hear a piece begin from somewhere in its middle. Williams was polite, funny, and very clear. Allowed to be in his presence while he was working was really quite an honor. It was such an honor that I instinctively knew not to clap when a piece ended. Unfortunately, some other attendees who were sitting directly behind me were oblivious to that and couldn’t resist clapping. Williams turned around and seemed to look straight at me: “Please don’t clap. We’re working here.” It took all of my self control not to stand up and say, “It wasn’t me!”

The music of John Williams also became a cherished companion on my various travels. I remember listening to “Summon The Heroes”, the theme from the 1996 Atlanta Olympics as my 2-year working holiday in the UK began on a rising 747 out of Sydney International Airport. The rousing piece helped lift my spirits and renew the promise of adventure that had been diminished by last-minute doubts.

Listening to Far and Away (1992) while walking along the Cliffs of Moher made the experience all the more memorable, and listening to Schindler’s List as I left Dachau concentration camp was I think the most I’ve ever been moved by a piece of music. Of course, I was already quite emotional; overwhelmed is a better word: visiting Dachau isn’t exactly a walk in the park. On a less depressing note, safariing throughout Africa to the strains of “Dry Your Tears, Afrika” from Amistad (1997) added significantly to the experience. In fact, two of my favorite photos from that trip show me in Uganda sharing Williams’ music with some of the sweetest kids I’ve ever met:

Like with most things, the arrival of the Internet changed everything. The Internet, as far as I was concerned when I first started using it, consisted only of hotmail and a John Williams fan site. This is how that site, The John Williams Fan Pages, looked back in 1999, some three years after I first discovered it. Considering that the site hasn’t been updated since 2008, it’s surprising it’s still online.

The second site, The John Williams Fan Network, was created in either late 1998 or early 1999 during the lead up to the release of The Phantom Menace to help connected fans worldwide anticipate, discuss, argue, and experience the first new Star Wars score in 16 years. Here is how it looked according to the Internet Archive’s earliest capture back in 2001. That site is still alive today, and its forums are quite active. Although active, the number of active members doesn’t feel that large to me. Perhaps 30-40 frequent posters, most based in the US or Europe. I visit the site every day, but probably only post once of twice a month. You can imagine my complete surprise than when, at a recent party I attended in Seoul, I was asked if I was the Peter who posts there.

Thanks to the Internet in general and those sites. I could now read about future Williams projects and re-releases of earlier works months in advance. I could also communicate with a strange and unique group of human beings I had yet to encounter in real life: people who liked soundtracks. There was, however, a very slight downside: my days of finding undiscovered gems in CD shops were numbered as were those CD shops.

My most memorable of experience of finding an undiscovered gem was coming across the 1993 Star Wars 4CD box set. Since it predated the Internet, I had no idea it existed until I came across it in Belconnen Mall. I still have the booklet with me in fact. It was that booklet that first informed me of Lukas Kendal who ran a monthly magazine that would later become the website Film Score Monthly. Upon reading of the existence of a magazine for film score fans, I ran to my local newsagent to place an order. The newsagent had never heard of it and neither had his computer system. Getting hold of an issue of Film Score Monthly proved to be mission impossible.

But the loss of such surprising finds was a small price to pay for all that the Internet would come to offer. As I mentioned before, I didn’t know very much about the composers I admired other than their names and the films they scored; they were essentially just faceless names on CD covers. YouTube enabled me access into their worlds via interviews with the composers themselves and with their musicians, footage from recording sessions, concerts, and even the opportunity to be a fly on the wall as Williams perform his new themes on piano for Steven Spielberg:

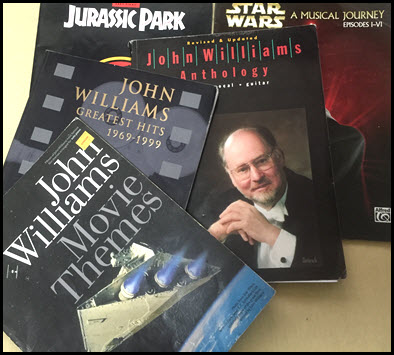

One aspect of my Williams fandom that related to my enjoyment of guitar was the growing availability of sheet music. Over the years, I built up something of a collection of John Williams music books of piano arrangements of varying difficulty levels. I would sometimes, with varying degrees of success, make my own guitar arrangements of the more accessible and less complex pieces. “Luke and Leia” from Return of the Jedi was one piece I always enjoyed playing. I have forgotten most of it, but I intend to revisit it sooner rather than later.

Although the books contain, by necessity, stripped down and simplified arrangements, they offered a window into the John Williams art and genius. Reading those piano scores while listening to their orchestral equivalents was a fascinating but slightly unsettling experience. I say unsettling because it was like discovering the magician performing feats of wonder was really just using sleight of hand as opposed to genuine magic. Seeing the melodies written down made Williams appear more human and slightly less Godly. Those combination of black notes on paper felt like something that I could write. Of course I can’t, but their creation now seemed slightly less supernatural. I have most of those music books with me here in Korea.

Taking up the piano in 2010 was another milestone in my experiences and adventures with music. Although I grew up playing guitar, there was something about the piano that always intrigued me. I never learnt to play, but I remember being more in awe and envious of the skills of piano players than of guitar players. Despite that appeal, it never occurred to me to do anything about it other than to lament the fact I hadn’t taken up piano as a child and to sometimes tinker at a keyboard with one-finger attempts of John Williams’ more famous melodies.

In 2010, at the rip young age of 6 years younger than I am today, I passed a keyboard for sale in a department store and decided to buy it. I began practicing like crazy such classics like “Jingle Bells” and “Chopsticks”, but it was the music of John Williams that I longed to play, and that dream kept me practicing day in and day out, sometimes for minutes at a time. Finally, my nascent skills blossomed to the point where I could make passable attempts at selected pieces. Here are two favorites with apologies for the out-of-tune guitar. Its strings were very old – so old they couldn’t stay in tune for any length of time beyond a second, and I just wanted to get the video over and done with that afternoon. I replaced them the next day if that’s any consolation.

Still on books, my love affair with Williams’ music has led me to read and enjoy quite a few books I might not otherwise have read. I read Memoirs of a Geisha when it was first rumoured that Steven Spielberg would direct the film. Steven didn’t end up directing it, but Williams did end up supplying the music. I read the first three Harry Potter before the films came out, but I reread them when Williams came on board. I read Angela’s Ashes for the same reason and also the Philip K. Dick short story Minority Report, but I probably would have read that anyway being a sci-fi fan. I read Schindler’s List and more recently The Book Thief. Most recently, as Williams was recording the corresponding score, I read Ronald Dahl’s BFG.

Another book I read because of my Williams fandom is a book about the man himself, which is criminally the only one to date. Emilio Audissino’s John Williams’s Film Music explores the history of music and film before exploring Williams’ career with extra attention given to several of his iconic scores. If only there were more like it; I would kill for a 1,000 page biography. I’m sure there’s an alternative reality out there somewhere where such a book exists.

As I wrap up this longer-than-expected musical memoir, Star Wars: The Force Awakens is still a new score, yet just days after the world first heard it in December 2015, the 83-year-old was already hard at work on his next creation, Spielberg’s previously-mentioned adoption of Roald Dahl’s The BFG.

That promise of new music on the horizon has been one of the defining elements of my Williams fandom. Ever since I first began collecting his scores 26 years ago, there has always been the promise of new works not to mention releases and expanded releases of older scores and compositions. I feel very lucky and even blessed to have discovered at a young age my favourite composer at a time when he had so much music and so many productive years ahead of him. It is no understatement to say that the music of John Williams has enriched my life. I honestly can’t imagine life without my constant musical companion. If you have read this far, you know that goes without saying. Thank you, John.

I’ll end with two more videos: the first is my performance of the arrangement of love theme from Superman which led to my first two Williams CDs. The performance is horrible, but the memories that piece elicits are not, and most of them are described above. The second video does the piece the justice it deserves:

Finish.